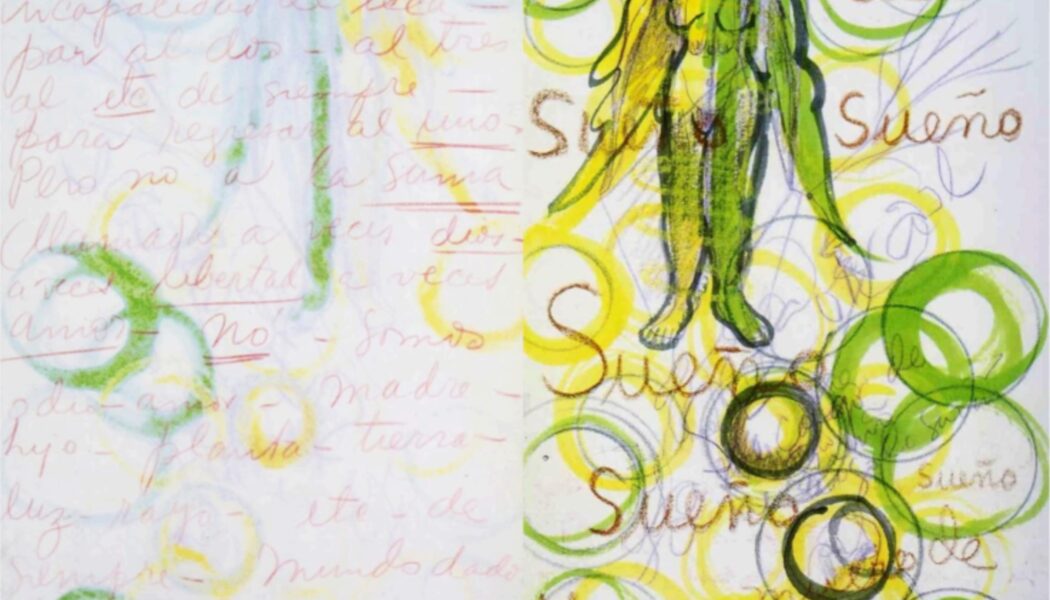

“ourselves –

variety of the one incapable of escaping to the two – to the three – to the usual –

to return to the one.

Yet not the sum (sometimes called God – sometimes freedom sometimes love – no – we are

hatred – love – mother –

child – plant – earth – light – ray – as usual – world bringer of worlds – universes

and cell universes – Enough!

Sleep

Sleep

Sleep

Sleep

Sleep

Sleep

I’m falling asleep”From The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait 1944-1954 (2005)

Frida Kahlo is often celebrated as a pioneering artist whose work powerfully reflects her personal experiences, struggles, and identity. As an important figure within magic realism, her paintings echo themes of pain, identity, and the duality of life and death. Kahlo’s spiritual perspective also featured a cornerstone that resonates with many modern thinkers: her atheism. While a lot of artists sought solace in religion, Kahlo forged her path through the lens of disbelief, drawing inspiration from her lived experiences rather than divine interpretations.

Kahlo’s famous “I paint my own reality,” captions her approach to both life and art. Kahlo’s rejection of the religious frameworks that dictate ethical and existential truths reflects a commitment to personal experience as the ultimate lead. This perspective resonates particularly well with atheist thought today, which advocates for a secular understanding of life and ethics derived from reason, empathy, and shared human experiences rather than divine decree.

To understand Kahlo’s atheistic thought and work, one must consider the historical and cultural landscape in which she was raised. The early 20th century in Mexico was marked by a deep sense of cultural identity following the Mexican Revolution, which led to a reevaluation of traditional values, including religion. Religion remained a central pillar of Mexican society, but numerous intellectuals, including Kahlo, began to question organized religious beliefs. Her secular thought was not merely philosophical but was also shaped by the influences of Marxism and communism that permeated her environment.

Kahlo’s life was marked by suffering, and her art often depicts the intersection of the physical and emotional pain she endured. For instance, her iconic painting The Broken Column (1944) visually articulates the agony of her lifelong battle with health problems. In grappling with mortality and existence, Kahlo found herself at odds with the established religious narratives that sought to offer comfort and explanations about suffering and the afterlife. Instead of looking for answers in faith, she embraced her disbelief, finding strength in her individuality and her heritage.

Kahlo, Rivera and Religion

Kahlo and her partner Diego Rivera stand as monumental in the world of art, embodying the complex intermixing of personal and political narratives. Their story is not merely one of love and companionship; it is also a vivid depiction of a tumultuous era in Mexico’s history, characterized by revolution and cultural renaissance.

Interestingly, while artists use imagery of saints or christian motifs to express existential themes, Kahlo’s and Rivera’s arts usually reflect a deep connection to Mexican folk culture and indigenous beliefs and even catholicism, juxtaposing them against their own atheistic stances.

Rivera famously wrote in a letter that he considers “religions to be a form of collective neurosis”:

“I am not an enemy of the Catholics, as I am not an enemy of the tuberculars, the myopic or the paralytics; you cannot be an enemy of the sick, only their friend in order to help them cure themselves.”

The unique blend of influences from Rivera’s “live and true” words to the Mexican culture and revolution, in Kahlo’s experience, allowed her to challenge both societal norms and the spiritual paradigms of her time. In fact, her relationships with both indigenous spirituality and leftist ideals suggest a complex understanding of the world that doesn’t confine itself to a binary view

of faith versus atheism.

Sigmund Freud’s exploration of the unconscious mind, along with his emphasis on the individual’s psyche over traditional dogmas, provided Kahlo with a different lens through which to view her own life and existence. His belief that neuroses were often rooted in the repression of desire and memory can be seen as a useful framework for understanding the intense emotions

and struggles that permeated Kahlo’s work. This intellectual exploration likely encouraged her to

confront, rather than flee from, the darker aspects of her existence, thus cultivating a form of

introspection that valued personal truth over religious obligation.

Frida Kahlo’s secular disbelief is not merely a rejection of faith but an affirmation of her identity and an expressive tool in her artistic journey. One finds a kindred spirit in Kahlo’s fierce individuality, her grasp of cultural legacies, and her unwavering commitment to live authentically. It’s clear that Kahlo remains a vibrant symbol of resilience, creativity, and disbelief.