Humanists International’s worldwide survey of discrimination and persecution the Freedom of Thought Report, continuously ranks Turkey as having “systemic discrimination” where disbelief often leads to cultural alienation. In time, situations of discrimination that create and maintain atmospheres of cultural ills for freedom of belief and expression, lead to individual and cultural harm.

Stigmatization of disbelief is not solely an escalating Turkish issue. According to the American Atheists and the Freedom of Thought surveys from the 2020s, the hegemonic culture in the United States demonizes disbelief.

The right to have or not to have a religion is a basic human right. Ensuring disbelievers have the same and equal rights with all the citizens of the world – with or without a particular religious inclination – would require globalized legal and cultural structures.

Accepting and respecting all beliefs, including non-belief, is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Disbelief, i.e. atheist and non-religious inclination, is targeted for persecution in various nations, the most severe cases involving the death penalty. Discrimination in general is an issue of superstitions about evil, leading to a general mistreatment of disbelief, breeding anti-scientific notions about what it means to be human, more than a disbeliever.

Religious belief is one of the names attributed to the evolution of the human brain, human intercontextuality and co-activity in the human mind. The name “God”, like those of polytheistic deities, Shiva or Brahma and so forth, concern how these co-active regions of the human brain are communicating in everyday lives, where humans in history had to come up with pseudo-scientific theories.

Religious or irreligious, conservative or liberal? Science shows that the human brain does not activate different regions, but that the brain regions for religious beliefs are comparable with the regions for political beliefs in the brain.

Science is the unconstrained search of truth, the free exchange of ideas, and the thorough inspection of hypotheses and theories through empirical inspection. Scientific research must explore novel concepts, challenge established paradigms, and follow the evidence wherever these may lead, without fear of retribution or suppression for failing to conform to a particular religious or ideological orthodoxy.

In 2009, the cognitive neuroscience program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that, to the human mind, “God” seems to have the same effect as that of any other human. According to this study of religious and irreligious people, sentences like “God is by my side” and “God watches me” lit up the same areas of the brain that humans use to decipher the emotions, thoughts and intentions of other people.

Integrity of science is surely not without challenges. There is potential for bias, possibility of mistakes or misinterpretations, and influence of external factors like funding sources or political agendas. That’s why scientists at NIH continued research for two decades, equipping it to observe the obstacles and remain a steadfast, credible means of expanding the frontiers of knowledge.

Various forms of belief, including religious belief, may be modulated by a set of intermingled brain regions and cultural networks. The researchers look at the studies that use functional neuroimaging or electroencephalography to find religious belief-related brain regions and networks, and studies involving lesion mapping.

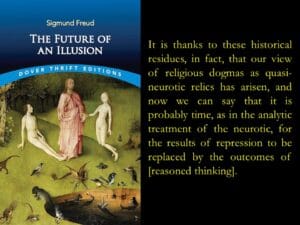

The continued research shows the fact that religions and ideologies aren’t scientifically different, and that economy-politics are involved in the process of beliefs. Karl Marx, like Sigmund Freud, did not have the cognitive scientific tools to observe the brain neurons when he made the allegory of “the opium of the masses”, “the unconscious human deeds,” and “false sense of consciousness” in the economy-politics of cultural evolution.

Sigmund Freud discussed this in his 1927 work, The Future of an Illusion. But Freud’s speculations of what was happening inside our brains would be less scientific, considering the technology to understand the neural activity was developed decades later.

Despite the rise of secularism and non-religious affiliations in a lot of countries, to be an open and vocal disbeliever means carrying a heavy social and even professional burden. Disbelievers are often viewed with suspicion, mistrust, and disdain, seen as immoral, untrustworthy, and lacking in ethics or values. This stigma stems from the deeply-rooted cultural and historical associations among religion, morality, and social cohesion – the notion that without belief in a higher power or divine authority, individuals will inherently lack a moral compass and the motivation to be good, upstanding citizens.